I’ll never forget the day when one of my esteemed pastors walked up to me and disapprovingly commented: “Is that a rock star haircut? Interesting.†Although I jokingly blew off his attack on my hairstyle choice, I knew from his response this was no laughing matter. I had clearly gone the way of the world. His comment made a somewhat spiritually mature twenty-seven year old feel like a spiritual infant. Should a simple hairstyle call into question my personal piety? Was I too hip to be holy?

Too Holy to be Hip

Peddle back with me to my first church in the 80s, known by its insiders as “The Mission.†I was the oldest kid in church, a single teen among adults and kids. I always wondered why there weren’t any other teenagers. As I matured, the reason became apparent. Not only were there no teenagers, there were rarely any newcomers. The Mission firmly believed its role in the kingdom of God was to pray for revival; that’s it. No evangelism, no cultural engagement, no social justice, and for many, no secular music, no television. On top of that, or should I say inside of it, there were the prophetic power brokers, whose super-spiritual connections led them to condemn certain people they deemed too “worldlyâ€. The Mission was hardly missional, too hollowed with churchly holiness to engage the “unholy cultureâ€. Their problem was the reverse—too holy to be hip.

The Church & Culture Pendulum

Noted historian Mark Noll has documented the 20th century pendulum of American evangelical postures regarding church and culture. In an article entitled “Where We Are and How We Got Here?â€, he demonstrates the absence of significant evangelical thought and action in the first half of the 20th century.[1] White American evangelicals abandoned serious engagement with academia, popular culture, and politics. The in-house fundamentalist-modernist controversy left fundamentalist Christians disconnected and quarantined from the ideas of the universities, the burgeoning impact of television, and civil rights legislature.

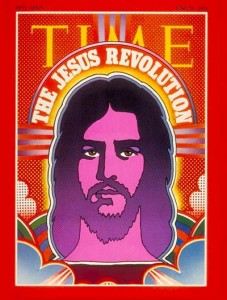

However, the second half of the 20th century presented a new evangelical—concerned, engaged, and actively influencing culture. Noll notes two key developments that contributed to a shift in evangelical posture towards culture. First, immigration reform led to an influx of de-Europeanized Christians, bolstering evangelical numbers. Second, the civil rights movement was launched from the southern African American evangelical church. As a result, American evangelicalism grew in number and influence. Subsequently, three culturally reforming movements followed—volunteer organizations (Young Life, Campus Crusade, Fuller Seminary), charismatic movements, and the Jesus People (Calvary Chapel).

Is Culture our Friend or our Foe?

Is Culture our Friend or our Foe?

The Jesus People rode the church and culture pendulum from quarantine to contextualization. Without quarantining themselves from hip-py fads and music all together, the Jesus People found a way to live out a contextualized 70’s gospel. They didn’t view culture as the enemy, but as a friend. Noll comments: “From the 1920s to the 1950s, American evangelicals had tended to view popular culture as an enemy—to keep the gospel it was necessary to flee the world. In the late 1960s, the Jesus People treated popular culture as a potential friend—to spread the gospel it was necessary to use what the world offered.†Friend or foe, hip or holy, quarantined or contextualized—do we have to choose?

[1] Mark Noll, “Where We Are and How We Got Here?†Sept 29, 2006, Christianity Today. See also George Marsden, Understanding Fundamentalism and Evangelicalism (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1991).

“The goal that diversity in secondary matters would be welcomed quite soon passed over into an attitude that evangelicalism could in fact be reduced simply to its core principles of Scripture and Christ. In hindsight, it is now rather clear that the toleration of diversity slowly became an indifference toward much of the fabric of belief that makes up the Christian faith.”

“The goal that diversity in secondary matters would be welcomed quite soon passed over into an attitude that evangelicalism could in fact be reduced simply to its core principles of Scripture and Christ. In hindsight, it is now rather clear that the toleration of diversity slowly became an indifference toward much of the fabric of belief that makes up the Christian faith.”